According to the Daily Telegraph, whilst at the Cheltenham Literature Festival, Mr Carluccio said: 'There was spaghetti Bolognese, which does not exist in Italy. In Italy, it is tagliatelle Bolognese, with freshly made tagliatelle and Bolognese without any herbs whatsoever.'

Mr Carluccio is just the latest to berate the British for taking a classic dish from abroad and subjecting it to unspeakable tinkering with the subtlety of a house decorator trying to restore a Michelangelo fresco. Poor Jamie Oliver suffered the wrath of Spain for the heinous crime of adding chorizo to his paella last week. And, according to Carluccio, the only way to cook a Bolognese is this:

'You should do this: oil, onion, two types of meat - beef and pork - and you practically brown this, then you put tomatoes, then a bit of wine, including tomato paste, and then you cook it for three hours. That is it. Nothing else. Grate Parmesan on the top and Bob's your uncle.'

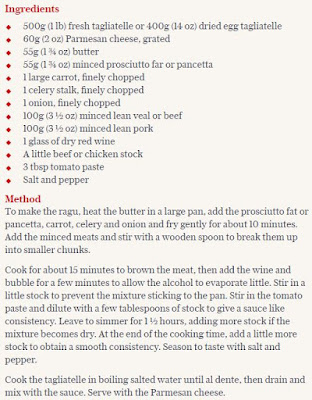

His argument is somewhat undermined by the fact that on the same page an entirely different Bolognese recipe appears, shorter but with more ingredients, by a chap called Antonio Carluccio:

But, is there, in Italy, an agreed way of cooking a Bolognese sauce? In 1982, the Bolognese Chapter of the Accademia Italiana della Cucina declared this to be the official 'classic' Bolognese ragu:

As with Carluccio's recipe, there are no herbs or garlic but it still differs significantly. And I doubt whether every household is equipped with the compulsory terracotta saucepan and a mezzaluna chopping knife.

But, here lies the problem: in Bill Buford's 'Heat' - a book which revels in the robust, macho, end of cooking - he writes 'there is not one Bolognese but many'.

'A Bolognese is made with a medieval kitchen's quirky sense of ostentation and flavorings. There are at least two meats (beef and pork, although local variations can insist on veal instead of beef, prosciutto instead of pork, and sometimes prosciutto, pancetta, sausage, and pork, not to mention capon, turkey, or chicken liver) and three liquids (milk, wine, and broth), and either tomatoes (if your family recipe is modern) or no tomatoes (if the family recipe is older than Columbus), plus nutmeg, sometimes cinnamon, and whatever else your great-great-great-grandmother said was essential.... In any variation, the result is a texture characteristic of all ragu: a crumbly stickiness, a condition of being neither solid nor liquid, more dry than wet, a dressing more than a sauce.... Gianni speaks of the erotics of a new ragu as it cooks, filling the house with its perfume, a promise of an appetite that will mount until it's satisfied.'

Later in the book, Buford cooks an eight-hour Ragu alla Medici which used red onions, garlic, as well as the usual suspects, carrot and celery.

But, with such diverse opinions on the matter - while I appreciate Carluccio's frustration - hoping to maintain the purity of a dish to continue when, perhaps, it never truly existed in the first place, is tricky.

I had a quick look at recipes in a few cookbooks I have at home. Predictably they were all different.

Below is from the Prue Leith's & Caroline Waldegrave's 'Cookery Bible', in which Carluccio's 'no herbs' diktat is ignored and the addition of marjoram or oregano encouraged.

Elizabeth David, in her classic 'Italian Cooking', chooses to add chicken livers, as well as nutmeg, to the pot:

I found another from Sandra Totti's 'A Taste of Tuscany' - ultimately intended for a lasagna admittedly - which uses fresh basil, thyme and sage, as well as a bay leaf and a clove of garlic. Asking a few colleagues for their interpretations, variations included adding a bay leaf to the oil and mushrooms and even olives to a classic ragu and letting it cook for as long as possible; another might even use lamb, the addition of chilli and it's all cooked in 20 or 30 minutes. It may well be that there are wrong ways of making a Bolognese but it does seem that there are many right ways.

And, speaking personally, my Bolognese ragu often depends on how much time I have to prepare it. I use beef and pork, prosciutto, wine and, scandalously, some herbs, and try to leave it on the hob for as many hours as are available before the demands for food from my wife and children become impossible to ignore any longer.

I'm afraid, Mr Carluccio's vision of what an authentic Bolognese is and should be has pretty much evaporated in this country. It may once have been a dish which emerged from Italian families, with all the variance that entails, and Italian academics may once have wanted to codify exactly what it needed; but, it has taken on a different form in Britain. It is not the classic Italian dish it may once have been - as this is not Italy. The spaghetti Bolognese is a British dish now.

But, if there is one way in which the British 'spag bol' and the Italian ragu are still related - and this may not please Mr Carluccio - it is this; as Italian families had their own versions, often passed down through the generations, it seems there may be as much variety in the domestic kitchens of Britain. Some, even Mr Carluccio, might find quite edible.

No comments:

Post a Comment

The comments expressed do not necessarily represent the views of the blog.